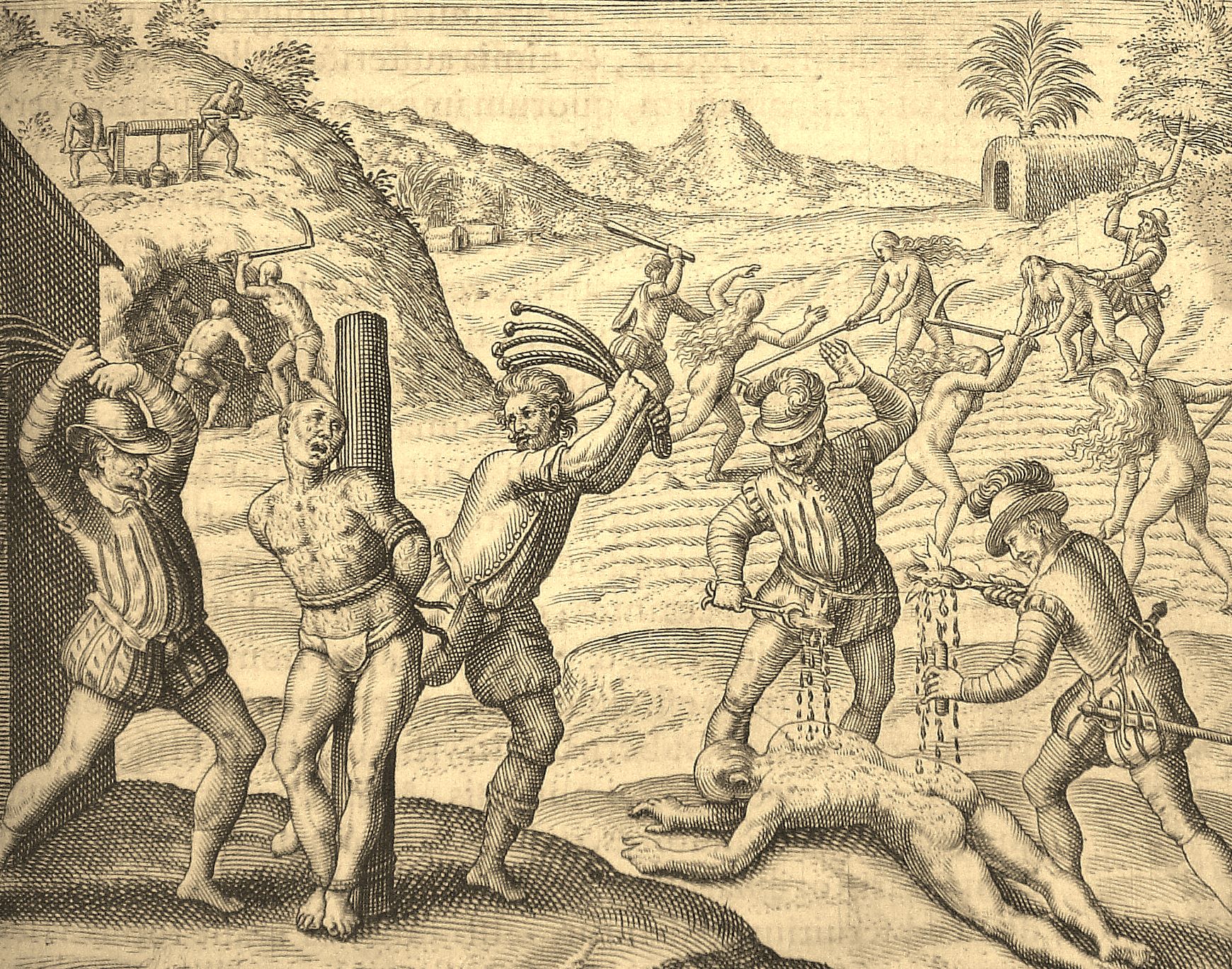

Like Antonio de Herrera, Lopez de Gomara never visited the New World. The conquest of the Weast India Ann Arbor, University Microfilms, 1966īorn at Seville, Spain, in 1510 de Gomara studied at the University of Alcala, was ordained priest, made a journey to Rome, and upon his return in 1540, entered the service of Hernándo Cortés as private and domestic chaplain. The New Laws of 1542, which were promulgated in large measure to mitigate the worst of colonial abuses of the native Indians, were a reaction to the revelations and uproar caused by Las Casas' published attacks and by his own single-minded determination to influence and reform royal policy.įrancisco Lopez de Gomara, 1511-1564. Herrera used the fact that Las Casas was allowed to publish his reports and dedicated them to the Spanish emperor as evidence of the Christian paternalism of the Spanish royalty towards her colonies. Antonio de Herrera, however, had access to his manuscripts, including that of a much larger unpublished work, Historia De Las Indias, which Herrera incorporated into his own history, softening the diatribes but preserving much of Las Casas' eyewitness accounts. Las Casas engaged in lively and sometimes heated debates with Spanish intellectuals and officials and his works were eventually suppressed in Spain. Las Casas, ironically, did more than anyone else to establish the “Black Legend” of Spanish cruelty which so inflamed violent anti-Spanish feelings in a Europe which felt besieged by Spanish troops and by Spanish ships on the high seas and the English Channel. It was translated into the various European languages (including this edition in English). Having spent much of his life in Mexico he wrote flaming, bitter denunciations of Spanish rule, filled with lurid first-hand accounts and depictions of the barbaric cruelties inflicted upon the Indians.

One of the most vitriolic and famous earlier accounts was written by Bartolomé Las Casas, a Dominican friar and later Bishop of Chiapas in Mexico entitled a Brief Relation of the Destruction of the West Indies, first printed in 1552. We see that history differently now of course, thanks to the rich culture and self-conscious historical traditions that developed in the former Spanish colonies but that earlier history remains part of our history and our European cultural baggage. In this Herrera preserved much history that would otherwise be lost. It is still extensively cited as a source, because Herrera included – and often plagiarized - accounts that no longer exist. It was the basis for several modern historical works in the 19th century. Herrera succeeded in writing a great history that has survived. It was to counter this propaganda that Phillip II suppressed many Spanish accounts and appointed Herrera as the official historian to produce a history that would silence Spain 's enemies. Accounts of Spain in the New World flooded the European book trade and fueled anti Spanish feelings. The Black legend derived in part from the Spanish themselves who wrote about their experience in the New World with a naïve egotism that was easily turned by European translators into the dark deeds of evil and cruel colonial slavers and tyrants.

This was Spain of the Black Legend as it came to be known, of Spanish domination, arrogance and cruelty This was Spain of the Counter Reformation and the Inquisition, the Spain which had annexed Portugal, and occupied Italy and the Netherlands. But Spain in the 16th century was the great European power and certainly to the other Europeans especially protestant Europeans, the great evil empire. Spain itself was in fact in decline and would continue so for a long time. T he glory days of Spanish conquest of the New World were long past when Herrera wrote his history almost two generations later. University of Nevada, Las Vegas Millionth Volume UNLV Libraries

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)